HOME ~ SMAD.INFO and Animals'

Enrichment

Animals

Choosing their Music

Many

places have let animals choose music to hear. A 2009 survey of 238 staff at 60 zoos worldwide found that 93%

of staff think auditory enrichment is "Important" for mammals,

but 74% never provide it, because of staff time constraints.

PRIMATES

Studies

vary on how much primates like music, and there are different ways to interpret

the studies. The researchers did important work to help animals choose, but it

is challenging. Humans gradually discover music we like over many years. We

vary a lot, get suggestions from others, and we have private spaces to enjoy

our choices without disturbing others. Most of us like some music and dislike

some, even within a genre.

Responses

of female rhesus macaques to an environmental enrichment apparatus

S.

W. Line, A. S. Clarke, H. Markowitz, G. Ellman

Laboratory Animals (1990) 24, 213-220

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1258/002367790780866245

Line

et al. mounted a radio on the cages of five single adult female rhesus

macaques. The radio was available for a 14-week period and was preset to a soft

rock music station; the animals could turn the radio on and off by touching two

different bars. Individual animals turned on the radio for 0–24 hours on

different days. Different animals averaged 3-15 hours per day over the

experiment as a whole, with the overall average of the 5 animals greater than

12 hours per day. Authors graph the total hours played by each animal each

week. The monkeys showed no signs of losing interest in listening to the music.

Chimpanzees

Prefer African and Indian Music Over Silence

Morgan

E. Mingle, Timothy M. Eppley, Matthew W. Campbell,

Katie Hall, Victoria Horner, and Frans B. M. de Waal,

Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition

emory.edu/LIVING_LINKS/publications/articles/Mingle%20et%20al%202014.pdf

A

2014 study found that 16 chimpanzees in Georgia stayed close to the loudspeaker

during irregular rhythms in some Akan music (Ghana) and Indian ragas more than

Japanese taiko, which has regular rhythms like the

western music used in Edinburgh. Each type of music was played 40 minutes on 3

different days. The first three days were controls, with a silent stereo,

followed by 9 days of music in random order. The researchers suggested regular

rhythms may be unpleasant, since chimpanzees use regular rhythms in dominance

displays, "stomping, clapping, and banging objects".

Music

as enrichment for Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii)

Sarah E. Ritvo and Suzanne

E. MacDonald, Journal of Zoo and Aquarium

Research 4(3) 2016

Toronto

researchers chose 210 pieces of music, from among the most popular on iTunes as

well as Tuvan throat singing, which is similar to orangutan long calls. They

played the first 30 seconds of each to 3 orangutans (separately), and after

each snippet, let the orangutan choose between a repeat, or 30 seconds of

silence, by touching the coloured half of a

touchscreen to repeat, or the grey half for silence. The 3 individuals chose to

repeat snippet of music 8%, 37% and 48% of the time. They had no chance to hear

the rest of the tune, or go back to a tune they liked a lot, as humans do.

It

would be interesting to give humans the same opportunity, and see how often

they ask for repeats, when listening to 30-second snippets of someone else's

choice of 210 tunes. All 3 orangutans "consistently displayed behaviours associated with orangutan distress"

throughout the touchscreen sessions, not unreasonably, given the frustrations

of hearing 30 seconds of random music 1,100 times. They pressed grey (silence)

more when especially stressed or distracted.

This

30-second approach may be an effective way to race through a lot of tunes to

find some tunes each orangutan likes. Whichever tunes they do like, there are

hundreds of similar ones which a service like Pandora or Slacker could offer,

to see how many of those they like. The researchers did not find any

consistency by genre, which is similar to humans, who may like some classical

tunes, or jazz or rock or folk, but not others. Even people who say they

"like classical music" often have preferences for romantic, baroque,

opera, modern, etc.

Is music enriching

for group-housed captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes)?

Wallace,et al, PLOS ONE, March 2017

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0172672

PMID:

28355212, PMCID: PMC5371285,

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172672

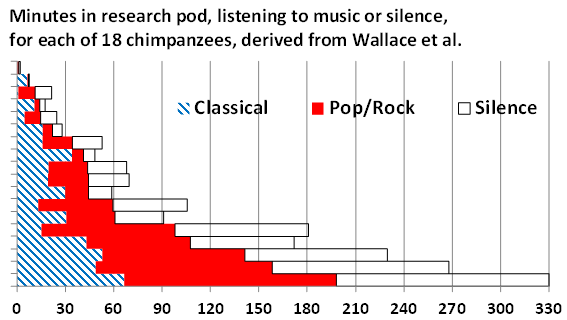

Another

group of researchers let chimpanzees in Edinburgh come and go from an area

where they played either silence or a rotation of 7 classical tunes, or 7

pop/rock tunes, which were very familiar, having been played more than 50 times

each in experiments in the previous two years. Chimpanzees varied widely in how

long they stayed in the small outdoor area where music played:

- 5

chimpanzees spent under 15 minutes where the music was playing.

- 3 spent

over 2 hours, out of about 4 hours when the music was playing.

- The other

10 ranged from 20 to 110 minutes, for a total of 18 chimpanzees.

The

wide range of time may mean the chimpanzees varied this much in how long they

wanted to hear these familiar tunes. On the other hand the chimpanzees who

listened the longest to music, also stayed longest during silence. They may

have liked the area or they may have hoped for the music to start again.

The

researchers tried to train the chimpanzees to choose for themselves whether to

have music or silence in the research area, by pressing symbols on a

touchscreen. However researchers were not sure the chimpanzees understood what

the symbols meant, since training only gave them 3-second bursts of music plus

half a grape each time they pressed any symbol. The 3-second bursts and grapes

may have squelched any intrinsic pleasure in the music.

Chimpanzees

could press symbols to turn music on or off, or switch between classical and

pop/rock, but could not pick individual tunes and could not select new music.

The researchers had removed dynamic range from each tune, "by reducing the

volume of loud passages and increasing the volume of quieter ones."

The

symbols were always in different locations on the screen, and symbols in the

final sessions were much smaller and squarer than they had been in training.

Any symbol preference may be for its appearance (zig-zags, stripes, or

bubbles), not for the 3-second snippets. If chimpanzees do not group genres as

humans do they would not realize there was a pattern where zig-zags gave them

classical music. After training, most button pressing was in the first session,

when they would have expected grape rewards, as they had in training. The

training and observations were in cold weather, January-April 2015, outdoors at

the Edinburgh Zoo.

McDermott

and Hauser:

Nonhuman

primates prefer slow tempos but dislike music overall Cognition

104 (2007) 654–668

Are consonant intervals

music to their ears? Spontaneous acoustic preferences in a nonhuman primate Cognition

94 (2004) B11–B21

The

title of their 2007 article, "Nonhuman primates prefer slow tempos but

dislike music overall", has been much quoted and has led trainers to avoid

playing music to primates. However if monkeys can turn music on and off, all

wanted music part of the time, even after a highly stressful introduction

to a new small cage.

Cotton-top Tamarin and Common Marmoset monkeys used body location to trigger the

researchers to change sound. Monkeys could see researchers, so could have

received unconscious cues ('07,

'04).

Experiments were done with varying numbers of 3 to 8 animals.

- Choosing

between silence versus lullabies or Mozart: individual tamarins and

marmosets spent 54% to 85% of their session with silence (p.663).

All the monkeys chose music some of the time.

- Choosing

between 60dB and 90dB white noise: individual marmosets spent 56%

to 69% of their session with 60dB.

- Choosing

between a flute lullaby and electronic techno at the same volume: on

average tamarins and marmosets spent 63% of their session with flute.

- Choosing

between 60 and 400 clicks per minute, on average tamarins and marmosets

spent 60% of their session with 60 clicks.

- Choosing

between 80 and 160 clicks per minute: on average tamarins and marmosets

spent 55% of their session with 80 clicks.

- Choosing

between recordings of tamarins' feeding chirps versus distress calls: on

average tamarins spent 58% of their time with chirps.

- Choosing

between consonant and dissonant 2-note chords: on average tamarins spent

51% of their time with dissonance (not statistically different from

consonant).

- Choosing

between white noise and steel scratching on glass: both at 80 dB, on

average tamarins spent 53% of their time with the white noise (not

statistically different from scratching steel).

Tamarins and Marmosets were measured when they were

highly stressed.

Researchers carried each animal to the entrance to a small cage with two

branches, left the room, opened the cage remotely, and in the next 5 minutes

the researcher played different sound depending which branch the animal was in.

They do not say how the animals reacted to being carried to the cage, but

"distress calls... screams [are] produced by [tamarins] being held by our

veterinary staff during routine checkups" ('04

p.B15), and, "Primates dislike being handled and are stressed by

it" (AWI

'15 p.176) so carrying them would leave them highly distressed for the next

5 minutes, during the experiment.

Researchers

do not say the cage size, but it appears about 25cm high. Tamarins average 23 cm,

and Marmosets 19 cm,

so they have little room, not "allowing the animals to move up to heights

where they feel secure" (Medical Research Council (2004) of the United

Kingdom, quoted in AWI

'15 p.176).

An

even more sophisticated system would add videos and/or games. Dr. Washburn's

2003 Presidential Address to the Southern Society for Philosophy and Psychology

said,

- "no

intervention has as potent an effect on rhesus monkeys' psychological well-being as does the

computerized test system [with joystick]. Although one can reduce the

symptoms of depression, boredom, and stress with other forms of

environmental enrichment (e.g., social housing, other toys, or manipulanda), the joystick-based apparatus and

game-like tasks have a substantial effect over and above these other

manipulations...

- "Of

course, joystick-based computer games are unlike anything that a rhesus

monkey would naturally encounter in its ecological niche. Rather than

supporting psychological well-being by making the laboratory more like the

wild, we have chosen to employ this highly unnatural technology to address

the basic factors of psychological well-being: comfort, companionship,

challenge, and control." ('03)

NON-PRIMATES

Dolphins used "a movable lever ... at night to turn on or off or

select among various tape-recorded acoustic stimuli, including dolphin sounds,

whale sounds, human voices, music, etc." (Herman, Cetacean Behavior '80)

A

captive Orca was observed to always

want new tunes, and objected to repeats. Orcas are far more acoustically sophisticated

than primates, but primates may have some preference for new tunes too, as

humans do.

Java

Sparrows

triggered a photosensor by sitting on a particular

perch, which determined which music was played. Two birds preferred Bach and

Vivaldi over Schoenberg or silence. The other two birds had varying preferences

among Bach, Schoenberg, white noise and silence. ('98)

Zebra Finches pecked levers

to play music, sometimes for hours, then stopped for hours. It appears each

lever played a short tune, which birds could and did repeat (no date).

Goldfish triggered Rite

of Spring , Bach Toccata and Fugue in

D Minor, or silence by presence in different thirds of a tank. The tank was

painted white to limit visual stimuli, such as experimenters' body language. A

camera and computer recorded fish location and played Bach if at one end,

Stravinsky if at the other end, and silence when in the middle. Only one of the

6 tested showed a preference for one end, where Rite of Spring played. All spent about 2/3 of their

time with music, 1/3 with silence, consistent with the music being in 2/3 of

the tank. ('09)

CONCLUSION

The

research projects here were staff intensive and gave limited times and choices

of music, because of time constraints. It is worth thinking what some ideal

systems might be, so research can see which work best for different animals:

- Quiet

speakers with individual controls so one or a few animals can choose what

to play without imposing it on others

- Buttons or

levers for: off, specific songs, new songs in a wide range of styles, with

a back button to go back to a previous song, and an algorithm or button to

update the specific songs

- Face

recognition or RFID to know which animal is at a speaker and remember what

it plays most, what it interrupts, and suggest new tunes, as Slacker and

Pandora do, with little need for staff maintenance.